THE MOCKUS INTERVIEW RETOLD

Professor Emeritus of Civil and Environmental Engineering

San Diego State University, San Diego,

California

PRELUDE

In the winter of 1993, the Late Pete Hawkins and I met in Denver

while we were both lecturing

at an Army Corps of Engineers' Technical Conference.

I had known Pete for a few years and was very familiar with his work.

It did not escape my attention that he had a good

track record on curve number hydrology.

Over the next two years, we toiled to complete the paper that we had set out to write.

Pete proved to be a meticulous coauthor; to this date,

my memory of the experience

still resonates positively in my mind. Pete needed to be convinced of my thoughts on the

subject; conversely, I may add, I needed to be convinced of his.

As planned, the paper went through the customary steps for

journal publication. There were three

discussions, to be duly followed by the authors' closure.

As

we prepared to write the closure, I had a

strong feeling that to do proper justice to the

methodology, we needed to get in touch with Victor Mockus,

Soil Conservation Service engineer of the 1940's, who was

widely recognized as a principal author. [In 1994, SCS

became the Natural Resource Conservation Service, subsequently to be

referred to as NRCS].

The original release of the methodology had been dated 1954. Vic

had retired in the 1960's, after a productive career in government service,

and ostensibly had been out of touch with SCS since then.

PREPARATION

I contacted Don E. Woodward, who at the time (1996) was

National Hydraulic Engineer at NRCS, for help in reaching Mockus.

Don encouraged me to do it,

but cautioned that it could be a slippery road, since about three decades had

elapsed and he (Don) understood that Mockus had not been in touch with SCS since

his retirement in the 1960's. I have always enjoyed a challenge.

At the time I

felt that if I was

successful in convincing Vic to briefly step out of his self-imposed

isolation, that our work would benefit inmensely, not to mention

the benefit to acrue to the profession at-large.

In July of 1996, I spent a few days in Washington, D.C., purposely to

interview Mockus. It did not take me too

long to find a working number for him.

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION

That evening, I prepared myself dutifully for the interview,

which was to take place the

following day.

THE MOCKUS RUNOFF EQUATION

The overriding question

in my mind, and presumably that of countless users of the curve number

method, was the origin of the so-called Mockus runoff

equation. In other words, how did Vic come up with

Eq. 3,

as shown in

Mockus proceeded with a calmness

that revealed that it was not the first time

that he had been asked the question. He

stated that he had zeroed in on that equation, "One evening, after dinner, seeing that it fitted the data very well, and after having tried many other alternative relations"

(NRCS: Miguel Ponce conversation with Vic Mockus).

It should be mentioned

that Mockus' equation unmistakingly states a complete opposite truth

to that of the classical Horton infiltration equation,

which preceded Mockus' work by more than two decades (Horton, 1933). Indeed, while Mockus' equation

states that retention and runoff are

directly related, Horton's equation states no such thing.

[We surmise that the recognition of this fact may

have been the source of many spirited arguments amongst scientists

in the early days of

infiltration modeling].

Herein lies the essence of the difference between these two historic approaches

to infiltration modeling, underscoring the intrinsic value and, therefore,

demonstrated permanence, of Mockus' approach

INITIAL ABSTRACTION

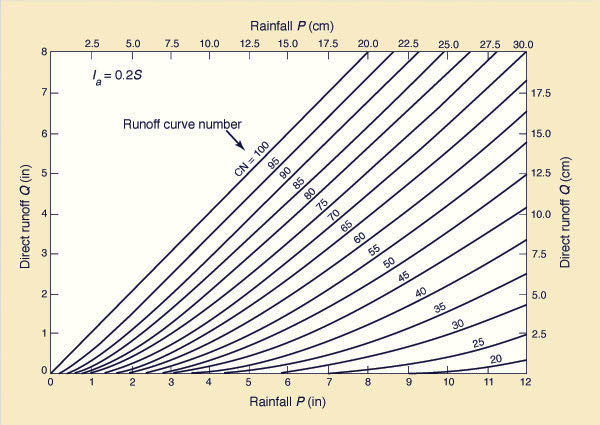

Initial abstraction Ia is

the rainfall which takes

place before the start of runoff; it is defined as Ia

= λ S, in which λ = initial abstraction ratio,

and S = potential maximum retention (of the study site).

The value λ = 0.2 has been used in the U.S. and most other countries

since its inception in 1954. However, Mockus was of the opinion

that if the data warranted,

the value could be changed to reflect local field

conditions. Extensive curve number experience,

particularly in the U.S. and other countries,

appears to point in that direction

APPLICABILITY ACROSS BIOMES

It was Mockus and his associates

who gave the method the name "runoff curve number,"

and this name

was

readily accepted for usage throughout the world.

Yet the method's paternity is recognized as SCS's,

which, four decades later, in 1994, became

NRCS. Thus, the method's original scope has been clearly defined

from the start:

Hydrologic modeling, with the objective of supporting

flood and erosion control studies

in small agricultural

watersheds. In the 1996 interview, Mockus noted that the field data used to

underpin the method's development

had varied in scale from 0.1 to 10 square miles. This fact all but reduces the

method's scope to direct runoff,

as opposed to

It is now widely recognized that the method's best performance is for agricultural watersheds, for which it was originally developed. The method's applicability has since

been extended to urban sites.

LIMIT TO WATERSHED SIZE

The comments of the previous paragraph take on a life of their own when

it is realized that, over the years since its introduction, the method's apparent simplicity

led to its wide popularity, which encouraged many

practitioners to apply

the method beyond its original scope, that is, for larger watersheds,

which were not necessarily of

agricultural type.

Mockus himself, when questioned on the practical upper

limit to watershed/basin size for use of the curve number methodology,

mentioned the 400-square mile

limit, in reference to the upper limit for midsize

watershed/basin runoff analysis

CURRENT MODELING PRACTICE

The NRCS runoff curve number method is now widely understood for what it is:

A rainfall-runoff model with a definite

conceptual basis, amply supported by field data, and officially

endorsed by a major federal agency. As Mockus stated

in the 1996 interview,

he saw no limit to a basin-scale application

of the runoff curve number equation, other than that which is

imposed by spatial rainfall uniformity.

Despite more than two decades of intensive research, the resolution

of the λ argument still awaits an official decision by NRCS (2026). A definite answer to this question remains elusive.

A change in λ from the current 0.2 value to

a possible future value of 0.05 will trigger a complete change in table runoff curve numbers, with the perceived reluctance to change of a long-established

practice.

REFERENCES

Hawkins, R. H., T. J. Ward, D. E. Woodward, and J. A. Van Mullem. 2009.

Curve Number Hydrology: State of the Practice.

Report of ASCE/EWRI Curve Number Hydrology Task

Committee, 106 p.

Hawkins, R. H., 1984. A comparison of predicted and observed runoff curve

numbers. Proceedings, Specialty Conference,

Irrigation and Drainage Division,

ASCE, 702-709.

Hawkins, R. H., 1993. Asymptotic determination of runoff curve numbers

from data. Journal of the Irrigation and Drainage Division, ASCE,

119(2),

334-345.

Horton, R. E. 1933. The Role of Infiltration in the Hydrologic Cycle.

Transactions, American Geophysical Union, Vol. 14, 446-460.

Ponce, V. M., and R. H. Hawkins. 1996.

Runoff Curve Number: Has It Reached Maturity? Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, Vol. 1, No. 1, January.

Ponce, V. M. 2014.

Engineering Hydrology: Principles and Practices, Prentice-Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, New Jersey, |

| 260209 |